The

Dams Raid : 617 Squadron : May 16/17, 1943

You

are welcome to email me but

remove the extra 'z' from the email address.

The

Plan Is Born

From

the early days of the Second World War (3rd September 1939) the brilliant,

if eccentric, scientist and aircraft designer Barnes Wallis was considering

ways to shorten the war. From the outset, the Mohne, Eder and Sorpe

Dams in the Ruhr presented attractive yet daunting targets, providing hydro-electric

power, industrial and domestic water and maintaining levels in canals which

fed materiel between factory and war depot. Destroying such targets would reduce

the enemy's capacity to wage war and such targets had been envisaged as important

since war loomed in the late 1930s.

The

massive Dams would be untouched by any bomb which RAF bomber aircraft of the

day could carry. The water at the dam face acted as an effective cushion between

the explosion and the dam wall, absorbing and dissipating most of the explosive

force, and it was impossible to drop a big enough bomb accurately enough to

cause a breach. Aerial torpedos were out; the Germans had stretched cable defences

and booms across the water. The lakes being land-locked, attack by submarine

was not possible.

After

exhaustive research into bomb types and explosive effects, Wallis discovered

that if he could make a bomb land up against the wall, the water cushioning

acted in his favour, tamping in the explosion and directing enough blast to

punch a hole. He smashed many model dams, and in early June 1942 destroyed a

disused real one (the Nant-Y-Gro dam near Rhayader, in Wales) until he found

the ideal size bomb. His problem was now one of placing the dropped bomb or

mine accurately.

In

July 2000, May 2006 and October 2018 I visited the site of the destroyed dam,

which is located in the picturesque Welsh hillside on the south bank of the

reservoir which is readily accessed via the Visitor Centre at Rhayader, this

being signposted from the town centre. The entire reservoir area is a

most beautiful series of hill walks and open to the public. In fact, the

handout describing the walks mentions the dam, which is clearly seen from the

public path. The actual dam is fenced off and to visit it in detail, permission

should be obtained to cross into the tiny valley in which it sits. (An

added bonus is overflights by RAF aircraft on training operations.)

Directions

: walk along the north shore and up to the large dam which overshadows the Visitor

Centre. Cross the river at the old pumping station bridge and make the

steep climb up the south shore to the large dam itself and go through the gate

at the top. Rest here after the climb, and admire the magnificent view

up the reservoir. Continue along the south bank, with the reservoir to

the immediate right, and follow this sometimes twisting footpath until it turns

left and climbs up with a small valley to the left. 200 yards up this,

as the little valley deepens, you will see the remains of the dam on the right.

On

the photo descriptions, "left"” and "right"”

are as viewed from the downstream or debris field side.

|

<

June 2006. The right hand remaining shoulder of dam wall, some

15 feet high from the footings, and the water-level remains of the dam

base, showing the debris field of large concrete chunks.

The

hole blown in the dam is about 30 yards across, and whilst at the time

of the explosion the dam was full, nowadays just a trickle of water runs

though the gap and down the small valley. Much debris is evident

on the downstream side, which drops away quite steeply to the reservoir.

Paul Brickhill in "The Dam Busters" describes the hole as 15

feet across and 12 feet deep, but he is notoriously incorrect on fine

detail like this. However, it is fair to comment that further collapses

may have occurred or been induced over the 58 intervening years, widening

the size of the gap stated by Brickhill.

A

visit to the site in October 2018 showed that the wall shown here is much

overgrown and almost invisible amongst the bushes and trees

|

|

October

2018 The left hand shoulder from the high valley side upstream

of it.

This

wall is also some 15 feet from footings to top level, and about 30 inches

wide at the top, quite enough to walk along.

|

|

|

|

This

is me against the remains of the wall; October 2018.

The

crack produced by the explosion is 4 to 6 inches wide and as can be seen

here, runs from the true shoulder of the dam to a point about 3/5 of the

way down the waterside wall.

|

Large photograph

(left, June 2006), showing the footings with water running

through, right hand shoulder of the remaining dam wall quite visible

and the concrete compensating basin in the immediate foreground.

The left hand wall

remains can't be seen from this angle. I did my best to get an

accurate then-and-now match, but found that if I matched the angle exactly,

overgrowth prevented anything like a decent view; so I stepped (slid!)

down the very steep bank about 12 feet, accounting for the different

perspective..

|

|

Compare

my 2006 photo above with the "official" monochrome one (left)

taken at the height of the explosion, June 1942. The compensating

basin is clearly seen, as is the intact dam wall, as the water plume is

driven skywards by the blast. Fractions of a second later, the wall

collapsed.

|

Using

an extremely large testing tank and various shape and weight golf ball sized

projectiles, he conducted many experiments, catapulting the missiles into the

water at varying speeds and angles until he could predict the length and height

of each bounce.

This

caused the model mine to skip over the surface of the water, avoiding the boom

defences, until it struck the dam face. Calculations showed that real drops

would have to be carried out at a strictly controlled speed, and at the very

low height of 150 feet. The mine was backspun before release and on impact crawled

down the face of the dam to explode at a preset depth. It acquired the codename

"Highball" for the scaled down anti-ship version and "Upkeep"

for the full sized weapon.

Although

a stress engineer and presented with many unfamiliar calculations and avenues

of research, by 1942 he was ready to ask for aircraft and other resources. His

idea seemed completely implausible to officialdom, and he was laughed out of

many a Governmental office. By sheer persistence and doggedness, and helped

by one or two sympathetic people, he obtained permission to build a scaled down

version of the bomb and allowed to convert a Wellington bomber to drop it. (He

had, incidentally, designed the Wellington.)

First

trials with a half sized mine proved successful and he obtained filmed proof

that the idea worked. But again the red tape was thick. Desperate, he persuaded

Vickers' chief test pilot, Mutt Summers to get him an interview with

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur T Harris, Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command.

Although Harris had previously described the idea as "Tripe of the wildest

description ... nobody would object to the Highball enthusiasts being given

one aeroplane and told to go away and play whilst we get on with the war",

he trusted Summers and was cajoled into watching the films taken at the test

drop and testing-tank. Afterwards Harris was non-committal, but about that time

Churchill gave the project his backing and in early 1943 Wallis was given

the official "go." With the need to attack the Dams in mid May when

they were full, this left little time to complete the project.

Harris

had been against the project from the start but was given uncompromising orders

from Sir Charles Portal, Chief of Air Staff and Harris's superior that the operation,

now named 'Chastise' should go ahead. Declining to withdraw an existing squadron

for special training, Harris decided to form a new Squadron of expert aircrews.

He assigned Air Vice Marshal the Hon. Ralph Cochrane, Officer Commanding

No 5 (Bomber) Group, to see to it. Cochrane had earlier supported Wallis's case.

"I've got a job for you, Cocky," Harris said, and explained.

Cochrane asked if he had anyone in mind to command the Squadron. Harris said

"Yes. Gibson." Cochrane agreed and sent for Wing Commander

Guy P. Gibson, then O.C. No 106 Sqdn flying Lancasters from Syerston. Gibson

had a long and satisfactory career as both a bomber and night fighter pilot,

and had won the DSO and bar and the DFC and bar and was about to finish his

third tour of operations. Sent for by Cochrane, and anticipating a long leave

in Cornwall, he was astonished when Cochrane asked him "How do you feel

about doing one more trip?"

Gibson

said "Yes" and he was caught up in a mad whirlwind of picking

his pilots and crew and the 1,001 details of forming a new Squadron. Given a

free hand, he chose some pilots he thought were the best, those who he knew

were very keen types and who would not baulk at the prospect of a dangerous

operation. However many of the personnel were unknown to him and some were even

on their first operation.

Guy

Gibson's mother Leonora came from a well known shipping family in Porthleven,

Cornwall and when staying there Gibson developed a love of the sea and sailing.

In a visit to the harbour in June 2012 I was pleased to see a plaque in remembrance

of Guy. This was placed in the wall of a chapel-like building which overlooks

the harbour, and is easily seen by those passing by on the pavement.

This

photo taken during the stormy weather in 2020 shows the chapel-like building,

and I have put the yellow star over the corner of the wall where the plaque

to Gibson can be seen.

I

am told that there is also a memorial to him in the local cemetery grounds.

The

Dams Crews : Avro Lancaster aircraft : Codes AJ

· Order : Pilot, Flight

Engineer, Navigator, Wireless-Operator, Bomb Aimer, Front Gunner, Rear Gunner

(mid upper turret not fitted)

This

excellent BBC News web site

shows photos of all the aircrew, and this one covers the 1955

Reunion. Another one shows the 1967

Reunion.

A FLIGHT : 'G' ED932 W/C

G P Gibson DSO DFC, Sgt John Pulford, F/O Harlo "Terry" Taerum, F/L

R E G "Bob" Hutchison DFC, P/O F M "Spam" Spafford, P/O

George A Deering, F/L R A D Trevor-Roper DFM. (Deering had been commissioned

before the operation, and Taerum promoted to F/O, without their knowledge.)

'A'

ED887 : Pilot : Squadron Leader Henry Melvin 'Dinghy' Young DFC & bar RAFVR

72478 [Killed]

Flight Engineer : Sergeant David Taylor Horsfall RAF 568924 [Killed]

Observer : Flying Officer Vincent Sanford MacCausland RCAF J/15309 [Killed]

Navigator : Flight Sergeant Charles Walpole Roberts RAFVR 1269945 [Killed]

Wireless Operator / Air Gunner : Sergeant Lawrence William Nichols RAFVR 1377941

[Killed]

Front Gunner : Sergeant Gordon Arthur Yeo RAFVR 1317656 [Killed]

Rear Gunner : Sergeant Wilfred Ibbotson RAFVR 655431 [Killed]

'B'

ED864 : Pilot : Flight Lieutenant William Astell DFC RAFVR 60283 (NCO:754517)

[Killed]

Flight Engineer : Sergeant John Kinnear RAF 635123 [Killed]

Navigator : Pilot Officer Floyd Alvin Wile RCAF J/16872 [Killed]

Bomb Aimer : Flying Officer Donald Hopkinson RAFVR 127817 (NCO:1036687) [Killed]

Wireless Operator / Air Gunner : Warrant Officer Class II Abram Garshowitz RCAF

R/84377 [Killed]

Front Gunner : Flight Sergeant Francis Anthony Garbas RCAF R/103201 [Killed]

Rear Gunner : Sergeant Richard Bolitho RAFVR 1211045 [Killed]

'J'

ED906 F/L David J Maltby DFC, Sgt W Hatton, Sgt V Nicholson, Sgt Anthony J Stone,

P/O Jack Fort, F/S V Hill, Sgt H T Simmonds

'L'

ED929 F/L David J Shannon DFC RAAF, Sgt R J Henderson, P/O Danny R Walker DFC,

F/O Brian Goodale DFC, F/S Len J Sumpter, Sgt B Jagger, P/O Jack Buckley

'E'

ED927 : Pilot : Flight Lieutenant Robert Norman George Barlow DFC RAAF Aus/401899

[Killed]

Flight Engineer : Pilot Officer Samuel Leslie Whillis RAFVR 144619 (NCO:998437)

[Killed]

Navigator : Flying Officer Philip Sidney Burgess RAFVR 124881 (NCO:1333022)

[Killed]

Bomb Aimer : Pilot Officer Alan Gillespie DFM RAFVR 144205 (NCO:1079863) [Killed]

Wireless Operator : Flying Officer Charles Rowland Williams DFC RAAF Aus/405224

[Killed]

Front Gunner : Flying Officer Harvey Sterling Glinz RCAF J/10212 [Killed]

Rear Gunner : Sergeant Jack Robert George Liddell RAFVR 1338282 [Killed]

'H'

ED936 P/O Geoff Rice, Sgt E C Smith, F/O R MacFarlane, Sgt C B Gowrie, F/S J

E Thrasher, Sgt T W Maynard, Sgt S Burns

'C'

ED910 : Pilot : Pilot Officer Warner Ottley DFC RAFVR 141460 (NCO:1332172) [Killed]

Flight Engineer : Sergeant Ronald Marsden RAF 568415 [Killed]

Navigator : Flying Officer Jack Kenneth Barrett DFC RAFVR 115775 (NCO:924924)

[Killed]

Bomb Aimer : Flight Sergeant Thomas Barr Johnston RAFVR 1060657 [Killed]

Wireless Operator / Air Gunner : Sergeant Jack Guterman DFM RAFVR 1172550 [Killed]

Front Gunner : Sergeant Harry John Strange RAFVR 1395453 [Killed]

Rear Gunner : Sergeant Freddie Tees RAF 1332270 [PoW]

'F'

ED918 F/S Ken W Brown RCAF, Sgt H Basil Feneron, Sgt D P Heal, Sgt H J Hewstone,

Sgt S Oancia, Sgt D Allatson, F/S G S McDonald

'K'

ED934 : Pilot : Pilot Officer Vernon William Byers RCAF J/17474 [Killed]

Flight Engineer : Sergeant Alastair James Taylor RAF 575430 [Killed]

Navigator : Flying Officer James Herbert Warner RAFVR 128619 (NCO:1222006) [Killed]

Bomb Aimer : Pilot Officer Arthur Neville Whitaker RAF 144777 (NCO:656416) [Killed]

Wireless Operator : Sergeant John Wilkinson RAFVR 1025280 [Killed]

Front Gunner : Sergeant Charles Mcallister Jarvie RAFVR 1058757 [Killed]

Rear Gunner : Flight Sergeant James McDowell RCAF R/101749 [Killed]

B FLIGHT: 'Z' ED937 : Pilot

: Squadron Leader Henry Eric Maudslay DFC RAFVR 62275 (NCO:920288) [Killed]

Flight Engineer : Sergeant John Marriott DFM RAFVR 1003474 [Killed]

Navigator : Pilot Officer Michael John David Fuller RAFVR 143760 (NCO:1151389)

[Killed]

Navigator : Flying Officer Robert Alexander Urquhart DFC RCAF J/9763 [Killed]

Wireless Operator / Air Gunner : Warrant Officer Class II Alden Preston Cottam

RCAF R/93558 [Killed]

Front Gunner : Flying Officer William John Tytherleigh DFC RAFVR 120851 (NCO:923074)

[Killed]

Rear Gunner : Sergeant Norman Rupert Burrows RAFVR 1503094 [Killed]

'M'

ED925 : Pilot : Flight Lieutenant John Vere Hopgood DFC and Bar RAFVR 61281

(NCO:1182427) [Killed]

Flight Engineer : Sergeant Charles Brennan RAFVR 942037 [Killed]

Observer : Pilot Officer John William Fraser RCAF J/17696 [PoW]

Navigator : Flying Officer Kenneth Earnshaw RCAF J/10891 [Killed]

Wireless Operator / Air Gunner : Sergeant John William Minchin RAFVR 1181097

[Fatal Injury]

Front Gunner : Flying Officer George Henry Ford Goodwin Gregory DFM RAFVR 141285

(NCO:755905) [Killed]

Rear Gunner : Pilot Officer Anthony Fisher Burcher DFM RAAF Aus/403182 [PoW]

'P'

ED909 F/L Harold B "Micky" Martin DFC, P/O Ivan Whittaker, F/L Jack

F Leggo DFC, F/O Len Chambers, F/L R C "Bob" Hay DFC RAAF, P/O B "Toby"

Foxlee DFM RAAF, F/S Tammy D Simpson RAAF

'W'

ED921 F/L J Les Munro, Sgt F E Appleby, F/O F G Rumbles, Sgt Percy E Pigeon,

Sgt J H Clay, Sgt William Howarth, F/S H A Weeks

'T'

ED923 F/L Joe C McCarthy, Sgt W Radcliffe, P/O D A MacLean, Sgt L Eaton, Sgt

G L Johnson, Sgt R Batson, F/O D Rodger. (MacLean had been commissioned before

the operation, without his knowledge.)

'S'

ED865 P/O Lewis J Burpee DFM RCAF, Sgt G Pegler, Sgt T Jaye, P/O L G Weller,

W/O2 S J L Arthur RCAF, Sgt W C A Long, WO2 J G Brady RCAF. (Arthur had been

promoted to W/O2 before the operation, without his knowledge.)

'N'

ED912 : Pilot : Pilot Officer Lewis Johnstone Burpee DFM RCAF J/17115 (NCO:R/82285)

[Killed]

Flight Engineer : Sergeant Guy Pegler RAF 573474 [Killed]

Navigator : Sergeant Thomas Jaye RAFVR 1299446 [Killed]

Bomb Aimer : Warrant Officer Class II James Lamb Arthur RCAF R/119416 [Killed]

Wireless Operator / Air Gunner : Pilot Officer Leonard George Weller RAFVR 142507

(NCO:1376022) [Killed]

Front Gunner : Sergeant William Charles Arthur Long RAFVR 1600540 [Killed]

Rear Gunner : Warrant Officer Class II Joseph Gordon Brady RCAF R/93554 [Killed]

'O'

ED886 F/S W C (Bill) Townsend, Sgt D J D Powell, P/O C L Howard, F/S G A Chambers,

Sgt C E Franklin, Sgt D E Webb, Sgt R Wilkinson

'Y'

ED924 P/O Cyril T Anderson, Sgt R C Paterson, Sgt J P Nugent, Sgt W D Bickle,

Sgt G J Green, Sgt E Ewan, Sgt A W Buck (Anderson had been commissioned before

the operation, without his knowledge.)

DID NOT FLY ON DAMS RAID DUE TO ILLNESS: P/O W G

Divall, Sgt D W Warwick, Sgt J S Simpson, Sgt R C McArthur, Sgt Murray, Sgt

E C A Balke, Sgt A A Williams

F/L

Harold S Wilson, Sgt T W Johnson, F/O J A Rodger, Sgt L Mieyette, P/O S H Coles,

Sgt T H Payne, Sgt E Hornby

(Anderson,

Divall and Wilson were later killed)

Returned to original unit after initial posting to 617

Sqdn: Sgt Lovell and crew

(back to 57 Sqdn); F/S G Lanchester RCAF and crew, the latter because Gibson

did not consider their navigator sufficiently skilled to handle what promised

to be a demanding operation, and the crew would not be parted from him. Paul

Brickhill in 'the Dam Busters' also describes a couple of the ground crew assigned

to the new Squadron crews as "outrageous duds" and Gibson himself

was equally scathing, taking pleasure in returning the two men to their previous

unit.

Training,

Security and More Problems

Equipped

at first with borrowed and later with their own modified Lancasters, the new

617 Squadron commenced flying training from RAF Scampton, the station commanded

by Group Captain Charles Whitworth. With everyone except Whitworth and

Gibson unaware of the real target, crews were delighted to be sent on long low-level

cross country flights; such were normally strictly forbidden. As proficiency

improved, night flying training was added. This proved very hazardous and the

answer was a training aid called "Two Stage Blue Day Night Flying"

where the pilots wore blue goggles and the cockpits were sheathed in amber screens.

This gave the effect of moonlight flying in broad daylight, yet the pilots could

still see their instruments. It had been invented by two brothers, S/Ldrs Arthur

and Charles Wood.

Security

was extremely tight. 617 was supposed to be a normal Squadron; yet there were

too many well decorated and experienced operational crews for this to go unnoticed.

Gossip abounded, but the security held and although there were a couple of minor

breaches, Gibson's astringent way of dealing with them stopped any further lapses.

There seem to have been some inexplicable compromisations of security at higher

levels, but these did not reach enemy ears. At Scampton, the other residents,

57 Squadron, were at first amused and then annoyed by 617's apparent lack of

operational time. Called the armchair warriors once too often, the 617 officers

replied with a comprehensive de-bagging session which claimed many a 57 Squadron

victim.

Meanwhile,

full sized mines built by Wallis had been dropped and failed to work, either

breaking up on impact or refusing to perform properly. Strengthening the case

was not the full solution, and Wallis buttonholed Gibson after a disastrous

test drop at Chesil Beach. "I asked if you could drop the mine at 150

feet; can you do it at sixty feet?" Gibson shuddered. "That's

very low," he said, aware that 60 feet was about half the wingspan

of his Lancaster and at that speed and height a hiccough by the pilot could

put the aircraft into the water. "But they've given me some crack crews

so we'll give it a try."

Practice

failed to make perfect. Even Spam Spafford, Gibson's hard-bitten bomb

aimer, was shaken. "Christ," he said down the intercom as the

Lancaster just missed the water on a training flight, "this is bloody

dangerous." Eventually the technique of shining two fixed spotlights,

one from the nose, one from the belly of the aircraft, proved simple and effective;

the navigator leaned out into the Perspex cockpit blister and called directions

whilst the pilot tweaked the Lancaster's height until the two beams were alongside

in a figure-8 with the aircraft then steady at 60 feet. This technique had first

been used in World War I.

Bomb-release

accuracy was less than satisfactory until Wing Commander Dann, a sighting

expert, showed Gibson a simple triangulated wooden bombsight with two nails

at one end and a peephole at the other. Looking through the peephole as the

aircraft approached the target, the bomb-aimer pressed the release button when

twin towers on top of the dam were in line with the nails. Dummy towers were

built on the Derwent Dam in Derbyshire and Gibson found that the sight worked

immediately. It was so simple that individual bomb-aimers were able to make

their own; some even used string attached to the bomb-aimer's Perspex. Held

up to the eye and marked at the required position, it was equally effective.

With the height and sighting problems beaten, it was just a matter of the flight-engineers

jockeying the Lancaster's throttles to get the speed correct at 220 mph.

Normal

navigation was a serious problem at ultra-low altitudes. Navigators made maps

on rollers and drilled the bomb-aimers into giving precise pinpoints as the

aircraft progressed. Hampered by the poor performance of the then standard H.F.

voice radio, Gibson hounded his superiors until Cochrane produced VHF fighter

radio-telephones, improving voice communications dramatically.

Despite

changes to and tests with the weapon continuing until only days before the raid

was planned to take place, many problems were overcome and on the night of Sunday

May 16th 1943, 19 Lancasters took off for the Dams, in three waves; Gibson's

flight to attack the Mohne and Eder, McCarthy's to attack the Sorpe,

and a mobile reserve and diversionary force led by Townsend. A full moon

lit the night sky, making normal operations impossible. An apparently bad omen

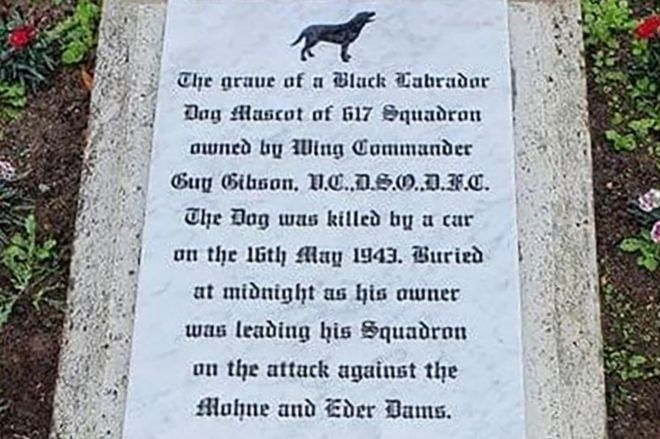

was that Gibson's black Labrador, Nigger, had been run over and killed

as the crews were being briefed for the operation. Gibson had given orders that

Nigger was to be buried at midnight on the grass verge outside his office; he

had the premonition that he and Nigger would be going into the ground at the

same time. The car's driver, a doctor from Grantham, did actually stop.

In

some versions of the film, especially those shown on TV in the last few years,

the dog's name is either cut out or voice-overed. I've even seen one version

which totally removed all the movie sequences featuring the dog, including where

he is run over and arrangements made for the burial, as well as edits where

the senior staff celebrate on receiving the code word by wireless message that

the Mohne Dam has been destroyed.

Yet

if you watch the film 'Gangs Of New York' the n-word is used throughout in violent

and threatening circumstances!

The

prospect of adjusting history in the interests of Politically Correct Stupidity

never ceases to amaze me. It is apparently PC to remind the Germans they lost

the war but not PC to say the correct name of a dog. In this context, who could

take offence? The editing required to eliminate the name of Gibson's dog also

results in some important tracts of the film being lost. It must be remembered

that at the time Gibson acquired his dog, this name was in common use for black

dogs and cats; and not considered to be derogatory or insulting.

Nigger's

grave can be seen on satellite images; Google Earth at 53.300827 / -0.549579,

or via What3Words.

RAF

Scampton was officially closed on Tuesday September 6th 2022. Nobody seems to

know what its fate will be or what will happen to the listed buildings or Nigger's

grave, althouht there are serious plans to turn the site into a holding camp

for the illigal immigrant invaders who cross the English Channel. H'mmm time

to drop a few Dams Mines on the rubber boats.

|

And

to cap it all, in 2020 the famous headstone at RAF Scampton was removed

and replaced with one which does not give the correct name of Gibson's

dog. And

to cap it all, in 2020 the famous headstone at RAF Scampton was removed

and replaced with one which does not give the correct name of Gibson's

dog.

Left

: before --- right : after.

Beware

a knock on your door from the Name Police, who want to know if you have

old copies of 'Enemy Coast Ahead' and 'the Dam Busters' they can confiscate

and destroy.

|

The

Operation

The

outward trip was flown all the way at low level and claimed 'B' (Astell)

who hit high tension cables and crashed at 0015, 5 km SSE of Borken; 'S'

(Burpee) hit by flak and crashed at 0200 near Gilze-Rijen aerodrome,

Holland; 'E' (Barlow) who crashed at 2350, 4 km ENE of Rees, also after

hitting high tension cables; and 'K' (Byers) was brought down by flak

at Texel. The Germans recovered Barlow's mine. All the crews were killed. Munro

in "W" was hit by flak over Vlieland and his intercom and radio

shot out; unable to communicate at all, he turned for home. Rice in "H",

using his belly lights to fix his height over the Zuider Zee, only found

out that the alignment had slipped when his Lancaster hit the water at over

200 mph, tearing out the mine. Dragging the Lancaster back into the air, he

too had to go home.

The

Mohne Dam was 900 yards long and 112 feet wide at its base. Gibson, giving instructions

on the crystal-clear VHF radio telephones with which the squadron's aircraft

had been fitted, grouped his remaining aircraft and made his bombing run, dropping

the mine accurately and under strong flak opposition; unfortunately the mine

sank about 50 yards short of the dam wall before exploding, causing no damage.

Once the spray cleared, Hopgood attacked, but was hit by flak, causing

the mine to overshoot the dam's parapet and explode directly beneath the Lancaster.

"Poor old Hoppy," said a voice on the radio; only two members

of the crew (Fraser and Burcher) escaped by parachute in the seconds

before the aircraft crashed. Martin attacked next and this time Gibson

flew alongside, helping to draw and disperse the enemy fire. Martin's Lancaster

was hit in an empty fuel tank; his mine exploded successfully but the drop was

inaccurate. The dam held. (Film buffs may care to note that the opening scenes

of the attack are repeated almost word for word in the film Star Wars

IV, as the rebel space fighters attack the Death Star.)

Gibson

and Martin both drawing the defences, Young went in next and dropped

his mine spot on the right place. Still there was no breach. Next was Maltby

who also dropped accurately and as the spray cleared, a 100 yard hole was

seen to open up in the dam wall, releasing 134 million tons of water. Shannon,

squaring up for his approach, was told to abort, and Gibson sent the others

home, taking his remaining aircraft on to the Eder, sending the code word

"Nigger" by wireless to show that the Mohne was down and instructing

Young to accompany him as deputy leader.

The

Eder, nestling in hills far deeper than anticipated, required the pilots to

dive steeply, level out and turn sharply at the start of the bombing run, then

try to lose a great deal of accumulated speed. Only 5 or 6 seconds were available

to do this. Shannon then Knight had great difficulty in losing enough

speed at the end of the diving approach and finding the right angle of approach

to the dam wall; afterwards it was necessary to pull up equally sharply to avoid

the hills. The whole attack needed airmanship of the highest order. There were

no defences; the Germans didn't think the Eder needed any.

Shannon

made several runs but was not satisfied and did not release his bomb. He then

asked for permission to reconnoitre. Gibson agreed and sent in Maudslay .

He too made several abortive runs before he seemed to have lost enough height

and speed, but he must have been going just a little too fast. The bomb overshot,

exploding on the parapet with the Lancaster directly above. Gibson, appalled,

called his friend. "Henry, Henry, hello Z Zebra, are you all right?"

A faint voice replied, "I think so - stand by." Maudslay had

been hit hours earlier on the way in over the Dutch coast, and several crew

wounded, but he had pressed on. Gibson called again, but there was no reply.

Critically damaged by the explosion, Maudslay turned the aircraft for home,

but crashed at Emmerich after being engaged by light flak. The entire crew were

killed. The couse being steered by Maudslay was a direct route from the Eder

Dam to his base at Scampton.

Shannon,

more confident, attacked and dropped his mine successfully. Knight attacked

next and had the same problem as the others; it was very difficult to lose the

speed incurred by the diving approach, then square up to the dam wall before

pulling up at the far end of the lake. Shannon gave advice over the radio and

Knight tried again, dropping his mine in the right place and as the explosion

cleared, the dam wall crumbled and 200 million tons of water cascaded through.

Gibson sent the code word "Dinghy" to indicate a successful

attack, and they all turned for home, there being no aircraft left to attack

the Sorpe.

McCarthy and Brown from the mobile reserve force both

attacked the Sorpe but this was a far different type of dam, requiring a totally

different attack technique. Unsurprisingly, it was not breached. Anderson

was directed to the Sorpe but due to heavy mist was unable to bomb and brought

the mine back. Ottley acknowledged orders to divert him to the Lister

Dam but was shot down by light flak and crashed at 0235, 3 km north of Hamm;

only the rear-gunner, Freddie Tees, survived, but he was badly burned.

Gibson, returning home, saw Ottley's aircraft flying over Hamm at 500 feet and

fall, burning, to earth. Townsend was directed to and bombed the Ennerpe,

but this, too, resisted the attack.

The

defences were now fully alerted and flak hit Young as he crossed the

Dutch coast. He struggled on for a few miles before ditching off Castricum aan

Zee at 0258. Although he had sent an SOS, and had twice successfully ditched

in the past, the crew were all killed. It is likely that the picture of the

remains of a crashed Lancaster on p89 of LANCASTER AT WAR I (Garbett & Goulding,

ISBN 0 7110 0225 8, Ian Allan Ltd 1971) is that of Young's aircraft. The remaining

aircraft reached Scampton safely.

Aftermath

Wallis,

until then preoccupied with the scientific difficulties, was suddenly faced

with the human cost of the operation; eight Lancasters and fifty-three men had

failed to return. Gibson tried to console him without success, and eventually

Wallis was given medication to help him sleep.

Harris

now did everything he could to make it look as if he had supported the operation

from the start, despite the opposite being true. I have wondered why there was

not a crew or two briefed to occasionally drop a 'cookie' on the Dams repair

workings in later weeks and months; such would have severely hampered repairs.

But I suspect that this was not done simply because Harris, having disagreed

with the Dams Raid from the start, either vetoed the idea or such proposals

ended up in his waste paper bin.

Nearly

all of the men were decorated. Gibson received the Victoria Cross, Britain's

highest award for gallantry. Martin, McCarthy, Maltby, Shannon and Knight were

given the DSO; Hay, Hutchison, Leggo and Walker received bars to their DFCs;

another 10 DFCs and 12 DFMs were awarded, and Townsend received the rare award

of the CGM. At the Investiture, 617 were decorated en masse by the Queen; an

altogether doubly unique event.

A

great number of them later perished. Gibson was taken off flying and sent to

America on a show-the-flag tour which was very successful. It was a task which

he disliked, but approached with typical zeal. On return to England, he was

considered too valuable to fly operations and was restricted to flying a desk.

The divorce from operational flying, together with personal disorientation as

to his status now the furore of the dams raid was over, caused him great distress.

He

badgered Bomber Command to be allowed to operate again. Finally, after a personal

appeal to Harris, he was posted to an operational unit. On the night of 19/20th

September 1944, his Mosquito KB267 of 627 Sqdn crashed in Holland, killing Gibson

and his navigator, S/L Jim Warwick. The cause is unknown, but Gibson

and Warwick were very inexperienced on the Mosquito, and Gibson had not operated

for a very long time. He was out of practice.

Recent

research (October 2011) suggests that Gibson and Warwick's Mosquito was shot

down in error by Bernard McCormack, a 61 Sqdn Lancaster mid-upper air-gunner

who mistook them for a Ju88. He made a taped confession which after his death

came to light. This air combat event was also witnessed by another Lancaster

crew, both sets of airmen seeing the Mosquito crash and giving an accurate location.

No Ju88s were lost that night and none claimed a Mosquito victory. It is possible

that the 'blue on blue' friendly fire incident was covered up by RAF authorities.

His and Jim Warwick's graves at Steenbergen can be seen here.

Gibson's

crew were inherited by W/C George Holden, the next 617 C.O. and were

killed on the night of 15/16th September 1943, except for Pulford, who was killed

on 13th February 1944 with S/Ldr Bill Suggitt in a flying crash, and Trevor-Roper,

who died on the infamous Nurembourg Raid, 30/31st March 1944, then with 97 Sqdn.

Martin's crew survived except for Bob Hay, killed in a low level attack on the

Antheor Viaduct; Shannon and his crew also survived, as did those of McCarthy

and Munro.

Thanks

to Larry Wright of the Nanton Lancaster Society in Canada who noticed that I had omitted to say that

F/Sgt K.W. Brown, CGM, RCAF and crew (less Sgt. B Allatson), P/O Geoff Rice,

F/Sgt. W.C. (Bill) Townsend CGM and crew who also survived the war, although

Rice's crew were killed, and he taken prisoner of war, in December 1943.

Ken

Brown, CGM, the last of the Canadian pilots who took part in the Dams raid,

died on December 23rd 2002 in White Rock, BC, Canada, as the result of a heart

attack. Les

Munro died in his native New Zealand on 4th August 2015.

617

were the only unit operating over enemy territory on this overnight period,

but two other aircraft were also lost. A Stirling of 75 Sqdn experienced engine

failure and was abandoned by most of the crew in mid air over Stoke-on-Trent,

and the pilot, trying to crash land, was killed with one other crew member.

Also a Wellington of 466 Sqdn vanished without trace over the sea, south of

the Lizard.

Modern

Points of View

It

is trendy to denigrate the Dams Raid in particular and Bomber Command in general,

but in 1943 the Allies had very little way to prosecute the war. U-Boat losses

were mauling the Atlantic Convoys and taking awful tolls amongst ships bringing

vital materiel across from America. Night-time operations by Bomber Command

and daylight raids by the U.S. 8th Army Air Force were picking at Germany's

industrial capacity in tactical bombing and trying to destroy the morale of

the populace by carpet bombing of cities. Despite this, Germany's production

was still increasing, but at a rate hampered by air attacks.

Bringing

down the Ruhr Dams, despite the over 50 per cent loss rate sustained by the

attacking crews, was a most tremendous tactical blow to Germany and did colossal,

if temporary, damage. At home it was a most highly successful propaganda matter

and brought foremost the efforts of the RAF, bringing in volunteers and focussing

the population on the need to attack the enemy. Such successes were rare enough

for every possible publicity angle to be capitalised upon. At a time when there

weren't many other successes to write propaganda about, the Dams Raid caught

the public's attention. Even 70+ years on, the Dam Busters are still alive in

the hearts and mind of the world. The film, of course, has a lot to do with

this.

Here

is an excellent British Pathe newsreel of the film's premiere, with very many

people shown who were associated with the Dams Raid, including Eve, Guy Gibson's

widow. Martin Shaw's analysis of the Dams Raid and the film can be seen here.

The

Wellington aircraft used in the film has been moved from the RAF Museum at Hendon

and is still (November 2021) benefiting from extensive restoration work at the

Sir Michael Beetham facilities, Royal Air Force Museum at Cosford. There are

occasional 'open days' at the workshops, the next one being scheduled for November

2022; I will be there with my Losses Database and would be happy to meet correspondents

and answer any queries I can.

Where

the British High Command failed was to follow up on the attacks. The Germans

moved heaven and earth to effect repairs, and these could have been bombed conventionally

on a 'nuisance' basis once in a while, preventing a complete repair and ensuring

that water supplies in the Ruhr Valley - Gemany's industrial heartland - were

short, as well as canals being starved of water. It is worth remembering that

the German canal system was instrumental in the movement of materiel, especially

prefabricated U-Boats.

One

correspondent says : "Bill Townsend (O for Orange) ended up working

for the Civil Service. I had the privilege of working with him at Bromsgrove

Unemployment Benefit Office in 1981. I remember him as being very quiet, but

a true English gentleman. At the time, I didn't know who he was, as he never

spoke of his background; but a few years later he died and the RAF did a flypast

at his funeral. It was then that I found out who he was and what he had done."

I

call the Dams Raid a resounding success, a triumph of British & Commonwealth

determination, and I salute the men and women who brought it about.

Reading

"The

Dam Busters" by Paul Brickhill.

The edition I have is a very loved and battered 1952 copy by the Companion Book

Club, but I have several. Brickhill is often inaccurate or wrong on the fine

detail, but it should be borne in mind that the book was written well before

serious research had been done into the topic.

"Enemy Coast Ahead"

by Guy Gibson VC DSO DFC. My edition is the Goodall one, ISBN 0 907579 08 6,

but I have several. A compulsory read, especially the 'Uncensored' version.

"The Dambusters Raid" by John Sweetman, pub. Arms & Armour, ISBN 18540090607. Exhaustively

researched to the point of being a technical manual, this book is required reading

on the subject.

"Chastise"

by Max Hastings, pub. William Collins 2019, ISBN 978-0-00-828052-9. A most comprehensively

detailed description of the entire operation from its inception to its aftermath,

this book is the one I most recommend.

"Bomber Command Losses 1943" by Bill Chorley, Midland Counties Publications , ISBN 0 904597 90 3.

"Guy Gibson" by Richard

Morris, Penguin Books, ISBN 0 14 012307 5. Read this one.

"Born Leader" by Alan

Cooper, Independent Books, ISBN 1 872836 03 8. Don't bother with this one.

"Dambuster,

a Life of Guy Gibson" by Susan Ottaway, Pen and Sword Books 1994/6,

ISBN 0-85052-503-9

You are welcome to email me.

And

to cap it all, in 2020 the famous headstone at RAF Scampton was removed

and replaced with one which does not give the correct name of Gibson's

dog.

And

to cap it all, in 2020 the famous headstone at RAF Scampton was removed

and replaced with one which does not give the correct name of Gibson's

dog.